You might not know that one of the things I have developed a deep passion for over the past 20 years or so is football. Soccer. Association football. Fütbol. It started when I lived in the UK as a kid and supported our local team Tottenham Hotspur. It waned a bit during the 1980s and 1990s when it was hard to watch games and no one in Canada really cared about the sport. But one of the great gifts of the internet was rekindling familiarity with the sport that I love. I love it for so many reasons, not the …

Share:

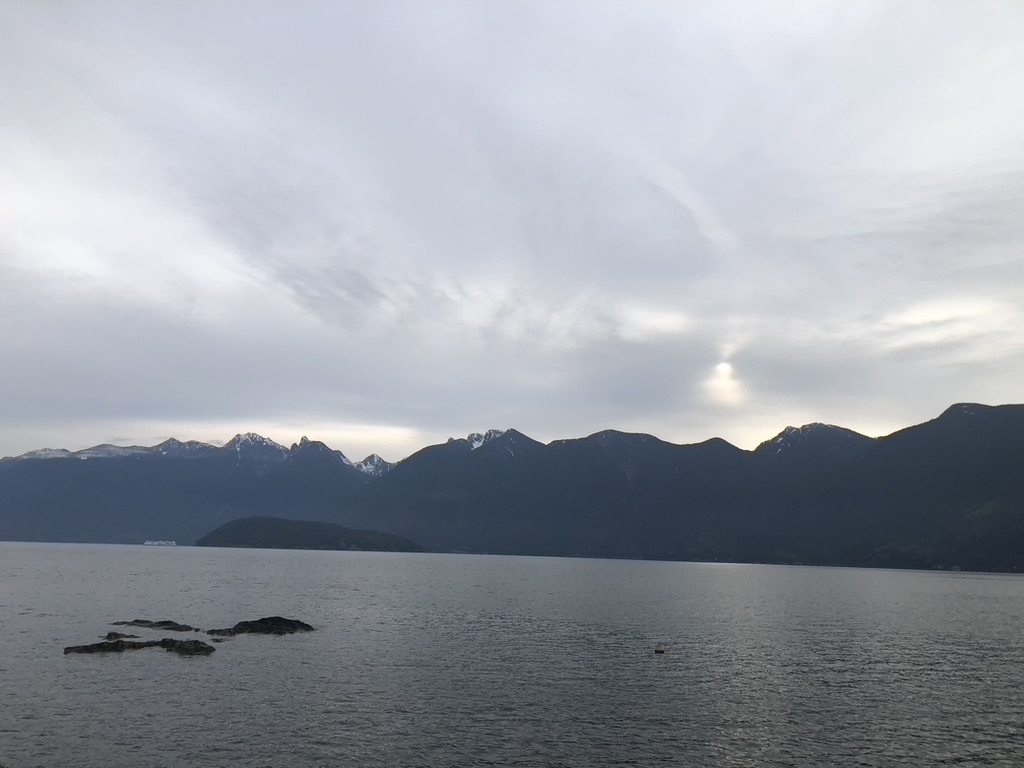

I live about 60 meters above the sea, facing southeast on the side of a mountain that is covered in Douglas-fir trees. My mornings at this time of year begin with light in my windows by 5am and the air full of birdsong. Up here, we are perched in the canopy of the forest and if I look out towards the sea, I am looking through to tops of tree that are 40 or 50 meters tall. As I have grown older, my eyes are not as good as they once were and while I can spot movement in the …

Share:

“Many others have written their books solely from their reading of other books, so that many books exude the stuffy odour of libraries. By what does one judge a book? By its smell (and even more, as we shall see, by its cadence). Its smell: far too many books have the fusty odour of reading rooms or desks. Lightless rooms, poorly ventilated. The air circulates badly between the shelves and becomes saturated with the scent of mildew, the slow decomposition of paper, ink undergoing chemical change. The air is loaded with miasmas there. Other books breathe a livelier air; the …

Share:

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about how the nuthatches have disappeared from my home island this year and how I was missing their little calls. Today,fromt he other side of the world a friend shared with me a watercolour he made inspired by that post. And so, through relationship and connection across time and space, one nuthatch has re-appeared on Bowen Island, , early on a holiday morning.

Share:

It is apparently International Tea Day, and my friend Ciaran Camman sent along this beautiful twitter thread describing tea culture across the Muslim world. It put me in mind of some memorable cups of tea I have had in my time: I fell in love with Turkish tea culture sipping tea from tulip glasses in Istanbul, during summer downpours in Taksim, by the side of the Bosphoros, or in the quiet back alleys of the old town as the calls to prayer echoed through the streets. Or on a gullet in the quiet waters off Demera, or in the mountains …